Pros & Cons of Industrial Sewing Machines

Parsing out the reasons why someone would want to add an industrial machine to their sewing arsenal.

Greetings everybody,

In this edition of The Sewing Machine Newsletter, we are going to examine the pros and cons of industrial sewing machines. Whether or not you are currently in the market for an industrial machine, I believe the following information will illuminate certain aspects of sewing machine design that are important, but often go unnoticed.

I hope you find it helpful.

PROS

When I think of the benefits of an industrial machine compared to a home sewing machine, it boils down to 3 main points of emphasis:

Ability to penetrate heavy fabric.

Ability to set knot with heavy thread.

Ability to feed heavy material.

(1) Ability to penetrate heavy fabric

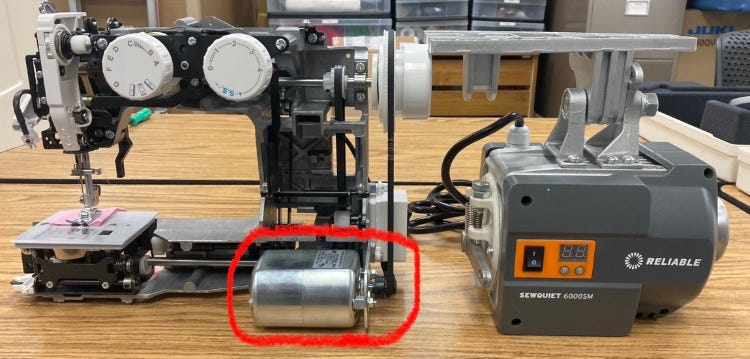

Industrial machines are more powerful than domestic machines. Part of that power differential comes from the difference in motors. Look at the photo below. On the left, I stripped down a home sewing machine that is designed with a quality motor that is quite common (motor circled in red). On the right is the brushless servo motor that powers our industrial machines. It is massive in relation to the domestic machine’s motor, and the power differential is massive as well. The domestic machine has a 60-watt motor, while the industrial motor is 550 watts.

The motor is not the only component that is more robust on industrial machines. The needle bar, the upper and lower shaft, the feed dog mechanism, the hook mechanism, the needle itself— all of these components are larger on industrial machines than on home sewing machines. The conjunction of quality heavy-duty components with a powerful motor allows an industrial machine to easily penetrate heavy material that a home machine would typically struggle with— multiple layers of thick leather, canvas, vinyl, etc.

The importance of a machine being able to penetrate the material is paramount. After all, the stitch is made below the needle plate, when the needle does its dance with the hook mechanism and bobbin thread. Without the power to penetrate the material, the machine will never even reach the point where the stitch gets formed.

(2) Ability to set knot with heavy thread

A sewing machine makes a lockstitch between the bobbin thread and top thread. A lockstitch is essentially a strong knot, and we want that knot to sit between the multiple layers of material that we are sewing so that it can best hold that material together.

Remember, the knot (stitch) is formed around the bobbin case area when the needle goes down below the needle plate and does a dance with the hook mechanism. Then, as the needle journeys upward, the action of the take-up lever cinches the knot up into the fabric. The video animation below depicts this process beautifully:

More often than not, sewing heavy material requires that we use a heavier thread. By heavier, I mean that the thread in literally thicker than the thread you would typically use to sew quilts and other cotton goods. Unsurprisingly, using thicker thread means that the machine will form a physically larger knot.

When using thicker thread, home sewing machines have trouble setting the larger knot back up into the fabric. The main reason why it has trouble doing so is because of an insufficient take-up stroke. The distance traveled from the take-up lever’s bottommost position to its topmost position is not enough to adequately cinch that thick knot all the way up into the fabric. Instead, the knot will sit on the underside of the fabric like this:

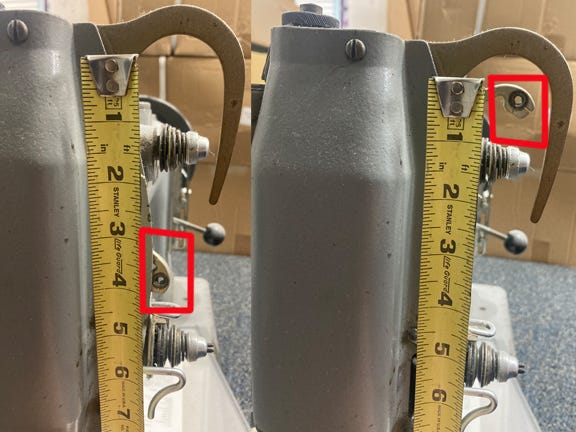

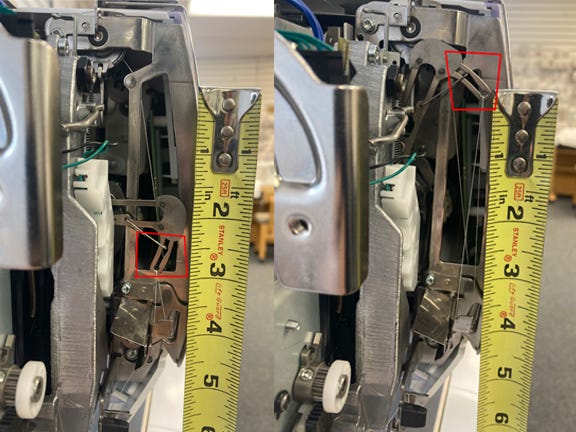

Industrial machines are designed to have a longer take-up stroke than a domestic machine—the distance travelled from the take-up lever’s bottommost position to its topmost position is long enough to cinch the knot up into the material properly. In the photo below, I measure the take-up stroke of an old Adler industrial machine. The take-up stroke is 4 inches long.

Compare that with the Bernina 770 Plus (in the photo below), one of the more powerful home sewing machines on the market. The take-up stroke is only 3 inches.

There are factors other than take-up stroke that also allow these industrial machines to successfully sew heavier thread. For example, a larger needle with a larger eye will handle heavier thread better than needles with a smaller eye. There will be less friction on the thread as it passes through the eye, which means there is less of a chance that the thread will shred or snag and affect stitch formation.

I’m on the verge of going down a rabbit hole, so I’ll move on after this last point— As you’ve heard me say already, in order for the stitch to form properly the thread must do a somewhat complicated dance around the hook mechanism (below the needle plate). Excuse the corny metaphor, but industrial machines are designed with a less crowded dance floor. There is more space for heavier thread to do that dance successfully. There is no free-arm to squeeze parts into, no zig-zag mechanism or auto-thread trimmer to worry about. The engineers don’t have to compromise the design for these features, so they can focus on making a machine that does one thing extremely well: straight-stitch with power.

(3) Ability to feed heavy material

**There is an entire class of industrial straight stitch machines that are designed for sewing cotton and lighter weight material. However, here I am going to talk a class of machines that are intended to sew super heavy material, for those of you interested in doing leatherwork and other materials of the sort.

Just as they have the ability to penetrate heavier fabrics with ease, industrial machines also have the ability to feed heavy fabrics with surprising ease (some better than others). An industrial machine made for sewing thicker fabrics (such as car upholstery) will be designed with something called needle-feed, which is a completely different type of feeding system than a home sewing machine.

On a home sewing machine, the machine only feeds the fabric once the needle has exited the fabric and is in its highest position:

needle down - needle up - feed - needle down - needle up - feed … and so on.

On an industrial machine with a needle-feed design, the machine actually feeds the fabric while the needle is down in the fabric:

needle down - feed - needle up - needle down - feed - needle up … and so on.

Here is a video of an industrial needle-feed machine, so you can see what I mean:

Needle-feed is beneficial because the needle helps keep the fabric together as it is being fed. Now, the machine in the video above is a Juki DNU-1541, which is a walking foot industrial machine designed with needle feed. With the DNU-1541, in addition to the fabric being fed with the needle in the down position, the fabric is also being fed by both the feed dogs and the walking foot at the same time. This needle-feed walking foot design allows the user to sew through crazy thick fabrics with ease. The DNU-1541 in particular is the machine of choice for people who do upholstery. For example, we have an awesome customer who owns a business called Compass Canvas in Point Richmond, CA. They do all sorts of different marina upholstery with their stable of 5 or 6 Juki DNU-1541’s

I also want to give a shoutout to this dude Marcelo who bought a Juki DNU-1541 from us and used it to propel his small clothing business called RIDGEWORKS. He takes textiles from all around the world, some of which are pretty heavy with unusual characteristics, and sews them onto upcycled denim clothing to create these cool one-of-a-kind pieces.

CONS

I am going to try to make this section short and sweet, as the negatives of industrial machines are pretty straightforward.

1. Heavy, takes up space, not (easily) portable.

Simply put, industrial machines are big and heavy. The Juki DDL-5550, which is on the smaller side when it comes to industrial machines, weighs 75 pounds, and that’s just the head of the machine. Most industrial machines have a motor separate from the head. The motor is mounted onto the underside of a table, and that table is fairly heavy itself because it has to be substantial in order to bear the weight of the machine.

What happens if something goes wrong with the machine and it needs to be seen by a trained technician? Unless you know somebody who makes house calls, you have to lift out the head and bring it into the shop.

And, for anybody curious, the standard footprint for an industrial table is 48 inches long and 20 inches deep.

2. They (usually) only do one type of stitch.

Industrial sewing machines are super specialized. Typically, one machine does one type of stitch. After all, they are made for commercial use. In a factory, there would be an assembly line of straight stitch machines, then an assembly line of overlock machines, and so on.

That is all to say if you only have the budget and/or space for one machine, and you want/need to have zig-zag and buttonholes and that kind of stuff, an industrial machine is probably not right for you at this time. I meet a lot of people who want an industrial machine that does both straight and zig-zag, but these days it is next to impossible to find an affordable well-made modern industrial machine that does both straight and zig-zag. If you ever find a Bernina 217 for sale that is in working condition, hop on it. They are no longer manufactured and are relatively rare.

3. Less user-friendly than modern machines.

Most modern home sewing machines are equipped with features that make sewing less fussy and more fun— automatic needle threader, automatic thread trimmer, needle up-down, low bobbin indicator, etc. Most industrial machines do not have these features.

Another example: industrial machines take a different type of needle than a home sewing machine. The needle base of an industrial machine is completely round, unlike a home machine needle which has a flat side. When you insert a needle into a home machine, the general rule is flat side faces back. When the flat faces the back, the needle eye is properly oriented with the hook. However, on an industrial needle there is no flat, so the user has to position the needle to the proper orientation themselves. I point this out just because this difference in needle type often leads to user error.

In Conclusion…

A pattern I’ve noticed in life in general is that whenever I examine a specific subject matter, that subject matter is endlessly deep. Such is the case with industrial sewing machines. I feel like there is still a lot left to explore, but it will have to wait until a future article, perhaps a part two. Still, I hope you found this edition of the newsletter to be informative and helpful.

One thing I will say is that industrial machines are relatively inexpensive compared to domestic machines. For example, we sell that Juki DNU-1541 walking foot needle-feed machine for $2,200, and that price includes the head, table, and motor. It’s really not that bad for a machine that can sew genuine leather goods with ease.

The other thing I’ll say is that, generally speaking, industrial machines are a joy to sew on for people who like to sew and appreciate good sewing machines. They’re smooth, fast, strong, and deliver a beautiful stitch. If you’re curious about seeing the full scope of the sewing machine landscape, I recommend you find a local dealer and see if you can sit down to sew on an industrial machine. I am personally a fan of Juki and suggest you test-drive one of the following models: DNU-1541, DDL-8700, DDL-8000, or the J-150 (this last one especially for quilters).

Thank you for reading. I appreciate you all.

-Cale

Am just beginning to learn to sew and I loved how informative this article was. Thanks for sharing.

For my heavier sewing projects I use a "Chinese leather shoe patcher" hand crank machine which works very well for me. Small footprint, portable and cheap (readily available on Amazon for just over $100). A very crudely made machine that once cleaned up and tuned has worked very well for me. The 360° walking foot is very handy. I have sewn leather, canvas, rubber and even bound books with it. For the money I don't think it can be beat.